-

SCAM WARNING! See how this scam works in Classifieds.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

What does net neutrality mean to FC'ers?

- Thread starter FlyingLow

- Start date

duff

Well worn

Find a girlfriend.What can be done at this point to stop this madness?

Tranquility

Well-Known Member

I am a deficit hawk. The spending binge of our government is anathemic to me. I would go into detail on how we got here but would bore most of the readers so decline. But, politicians spend all they can here--plus a little more. Always. If taxes go up, spending will go up. The only way to deal with it is to starve the beast. While it may be hard to understand, the deficit will not decrease until spending is under control. The debt will continue to rise unless the country grows to cover it. (We might be able to inflate out of about a quarter of it.) It amuses me those who have been so keen on our spending binge for the last decade suddenly care about the deficit. I actually care and the scoring is always wrong.Yes, I agree with loopholes and manipulation... most tax systems are plagued with that. There is no perfect system, and in economics even though we hope that government polices lead to Pareto optimal outcomes it rarely does. But, this new tax reform in its original form will make the rich richer and the poor poorer, and shrink the middle class. Yes, there is a huge population that is uninformed, but does this mean that they should get shafted? I believe that a more stable society is where we can level the playing field not one that divides it. And that is what I mean by regressive. As for raising government revenue this new tax reform bill is predicted to add another $1.7 trillion to the deficit?!?

I'd go on but we change this into a tax discussion and would require details that are not useful in this format.

The bottom line is people generally fall into two categories. Those who think the government owns the fruits of our labors and who generously gives us some to live on and those who think we own the fruits of our labors and who gives the government some to run. As I've said before, this bill is going to be very expensive for me in the short run. (I didn't even talk about a real killer provision for people like me who perform professional services in a pass through.) Not in some theoretical way. Real. Money. Expensive. I still support the bill because I sincerely believe it will help the economy for everyone by removing a lot of issues in the tax code. Admittedly, just because they're going to screw my upper-middle-class income, service-professional-through-a-pass-through-who-owns-property-and-lives-in-a-high-tax-and-high-property-value-state-ass does not mean I get to bitch about it too much. I've done well under the old code. After a few years of changing my position after the law passes, I'll be fine under this one too. And, while my time might not be as gold-plated as before, I will still be able to realistically look towards retiring someday.

The solution to your claim of oligopoly (Which I don't take a position on but lean towards agreeing with.) is not net neutrality. That situation is unchanged with net neutrality. If there are monopoly issues, anti-trust law is the appropriate venue rather than having the government dictate information flow.I have to disagree. Yes there are about 20 ISP in the US, but 3 providers own about 65% of the market share. That to me is an oligopoly market structure, which is then susceptible to collusion/price fixing. The market for weed is similar to a perfect market structure and therefore market price prevails as no one has any market power; homogeneous product, perfect competition, and a large number of sellers.

Also the other big factor is price elasticity of internet services, an economic research firm found that the demand for internet services is quite price inelastic (elasticity coefficient is around .2) in most developed nations. So if price goes up people will still continue to demand internet services as it is now considered a necessity vs a luxury good. Thus regulation is necessary.

Tiny88

Deluxe420

I am a deficit hawk. The spending binge of our government is anathemic to me. I would go into detail on how we got here but would bore most of the readers so decline. But, politicians spend all they can here--plus a little more. Always. If taxes go up, spending will go up. The only way to deal with it is to starve the beast. While it may be hard to understand, the deficit will not decrease until spending is under control. The debt will continue to rise unless the country grows to cover it. (We might be able to inflate out of about a quarter of it.) It amuses me those who have been so keen on our spending binge for the last decade suddenly care about the deficit. I actually care and the scoring is always wrong.

I'd go on but we change this into a tax discussion and would require details that are not useful in this format.

The bottom line is people generally fall into two categories. Those who think the government owns the fruits of our labors and who generously gives us some to live on and those who think we own the fruits of our labors and who gives the government some to run. As I've said before, this bill is going to be very expensive for me in the short run. (I didn't even talk about a real killer provision for people like me who perform professional services in a pass through.) Not in some theoretical way. Real. Money. Expensive. I still support the bill because I sincerely believe it will help the economy for everyone by removing a lot of issues in the tax code. Admittedly, just because they're going to screw my upper-middle-class income, service-professional-through-a-pass-through-who-owns-property-and-lives-in-a-high-tax-and-high-property-value-state-ass does not mean I get to bitch about it too much. I've done well under the old code. After a few years of changing my position after the law passes, I'll be fine under this one too. And, while my time might not be as gold-plated as before, I will still be able to realistically look towards retiring someday.

The solution to your claim of oligopoly (Which I don't take a position on but lean towards agreeing with.) is not net neutrality. That situation is unchanged with net neutrality. If there are monopoly issues, anti-trust law is the appropriate venue rather than having the government dictate information flow.

I hope your support is warrant. However, I would be pissed that a tax reform would make me poorer while making the rich richer. I would want a government to take care of the disadvantaged and not give them the shaft, and redistribute income so that we have a more stable society. But to each each there own...

Last edited:

Tranquility

Well-Known Member

My point is, I am the "rich".I hope your support is warrant. However, I would be pissed that a tax reform would make me poorer while making the rich richer. I would want a government to take care of the disadvantaged and not give them the shaft, and redistribute income so that we have a more stable society. But to each each there own...

I have food in my refrigerator and clothes in my wardrobe so I am in the top 20% of the world.

My income puts me in the top 10% of the U.S.

Since I don't think not giving away my stuff to someone else who thinks they deserve it is giving them the shaft, I think it clear I am in the camp of I own my own labor. Wanting to redistribute income might put you in the camp of the government owning my labor. I don't think we will ever come to agreement on the best path forward. All we can really hope for is clarity on our positions.

Last edited:

Tiny88

Deluxe420

My point is, I am the "rich".

I have food in my refrigerator and clothes in my wardrobe so I am in the top 20% of the world.

My income puts me in the top 10% of the U.S.

Since I don't think not giving away my stuff to someone else who thinks they deserve it is giving them the shaft, I think it clear I am in the camp of I own my own labor. Wanting to redistribute income might put you in the camp of the government owning my labor. I don't think we will ever come to agreement on the best path forward. All we can really hope for is clarity on our positions.

Yes, I don't are too far off... we both want the world to be a better place.

okay, here's what loss of net neutrality means to me and my operation(s) ... it basically means Facebook advertising and Google advertising is worthless - if my ad is not being auctioned every-fucking-where, why advertise? So, basically, the carriers saw all this ad money pouring into FB and Google and said, damn! we can get a piece of all the pie.

and, i wonder if my website will disappear, or how much i must pay extra to get it delivered to some tier of browsers?

but, on the plus side, more carrier competition being stimulated, right? ... how hard can it be to set up a new internet backbone. hell, Microsoft just dropped a new transatlantic cable, in record time.

this could be a good model for the interstate highway system. auction off slots in the stream of self-driving vehicles.

i think the already evolved ad delivery systems can handle the pay-to-play nature of carrier access - kind of a micro-payment system, i guess.

but it's still early in this process, i am sure it can go much further south than i can possibly imagine.

and, i wonder if my website will disappear, or how much i must pay extra to get it delivered to some tier of browsers?

but, on the plus side, more carrier competition being stimulated, right? ... how hard can it be to set up a new internet backbone. hell, Microsoft just dropped a new transatlantic cable, in record time.

this could be a good model for the interstate highway system. auction off slots in the stream of self-driving vehicles.

i think the already evolved ad delivery systems can handle the pay-to-play nature of carrier access - kind of a micro-payment system, i guess.

but it's still early in this process, i am sure it can go much further south than i can possibly imagine.

hey! i wonder if this means the carriers can now be held accountable for delivering malware/hackers to my local network. they should only deliver sanctified packets ... or else.

the end of hackers is a good trade-off for the end of internet freedom ... can i get an amen?

the end of hackers is a good trade-off for the end of internet freedom ... can i get an amen?

Here in Canada ... I guess I'm likely in the top 10-20% too ... and I strongly believe in supporting the less fortunate through proper social/economic support systems, and taxation that favours the less fortunate, however, I feel like in Canada, the rich get richer, the poor get poorer, and the middle class pay for it all; I just wish the "rich" would pay their share as well (which should be greater since they have greater disposable income ... the middle class and poor just "get by" ... why can't everyone prosper in a country with so much wealth through natural resources and other?)

Oh well ... only see it getting worse in the near to mid future at any rate ...

Oh well ... only see it getting worse in the near to mid future at any rate ...

Dustydurban

Well-Known Member

Hyper ventalation helps no one

Paper sacks are over in the corner

Paper sacks are over in the corner

Tranquility

Well-Known Member

I'm sad/happy to say, my highly-paid lobbyists have been extraordinarily successful. When I wrote previously, I was on the wrong side of all limits and amounts and the law was going to kill me. Now, the thing that came out of conference makes me golden. There are still things that will make my position worse. It's just that the really terrible effects (from my point of view) won't happen to me now. It's like an early Christmas gift.

I have no idea of the payback's yet so don't know how they changed the limits to accommodate me and still stay within the scoring limits on debt. I can only imagine the reason for the changes was to smooth implementation of the taxes and have some of the more dire effects spread out.

I have no idea of the payback's yet so don't know how they changed the limits to accommodate me and still stay within the scoring limits on debt. I can only imagine the reason for the changes was to smooth implementation of the taxes and have some of the more dire effects spread out.

Tiny88

Deluxe420

I'm sad/happy to say, my highly-paid lobbyists have been extraordinarily successful. When I wrote previously, I was on the wrong side of all limits and amounts and the law was going to kill me. Now, the thing that came out of conference makes me golden. There are still things that will make my position worse. It's just that the really terrible effects (from my point of view) won't happen to me now. It's like an early Christmas gift.

I have no idea of the payback's yet so don't know how they changed the limits to accommodate me and still stay within the scoring limits on debt. I can only imagine the reason for the changes was to smooth implementation of the taxes and have some of the more dire effects spread out.

Hope you are right.

StormyPinkness

Rhymenocerous ʕ•ᴥ•ʔ

While this makes me glad I'm not with Comcast, I'm 100% sure my ISP will be doing the same shit. Shady website prioritization and throttling for all!

https://twitter.com/Zacilles/status/941441718095884289/photo/1

"Comcast's #NetNeutrality page before and after Ajit Pai first launched his plan to repeal the rules in April."

https://twitter.com/Zacilles/status/941441718095884289/photo/1

"Comcast's #NetNeutrality page before and after Ajit Pai first launched his plan to repeal the rules in April."

Silver420Surfer

Downward spiral

For years a lineup of phone- and cable-industry spokespeople has called Net Neutrality “a solution in search of a problem.”

The principle that protects free speech and innovation online is irrelevant, they claim, as blocking has never, ever happened. And if it did, they add, market forces would compel internet service providers to correct course and reopen their networks.

In reality, many providers both in the United States and abroad have violated the principles of Net Neutrality — and they plan to continue doing so in the future.

Here’s what happens when cable and phone companies are left to their own devices:

MADISON RIVER: In 2005, North Carolina ISP Madison River Communications blocked the voice-over-internet protocol (VOIP) service Vonage. Vonage filed a complaint with the FCC after receiving a slew of customer complaints. The FCC stepped in to sanction Madison River and prevent further blocking, but it lacks the authority to stop this kind of abuse today.

COMCAST: In 2005, the nation’s largest ISP, Comcast, began secretly blocking peer-to-peer technologies that its customers were using over its network. Users of services like BitTorrent and Gnutella were unable to connect to these services. 2007 investigations from the Associated Press, the Electronic Frontier Foundation and others confirmed that Comcast was indeed blocking or slowing file-sharing applications without disclosing this fact to its customers.

TELUS: In 2005, Canada’s second-largest telecommunications company, Telus, began blocking access to a server that hosted a website supporting a labor strike against the company. Researchers at Harvard and the University of Toronto found that this action resulted in Telus blocking an additional 766 unrelated sites.

AT&T: From 2007–2009, AT&T forced Apple to block Skype and other competing VOIP phone services on the iPhone. The wireless provider wanted to prevent iPhone users from using any application that would allow them to make calls on such “over-the-top” voice services. The Google Voice app received similar treatment from carriers like AT&T when it came on the scene in 2009.

WINDSTREAM: In 2010, Windstream Communications, a DSL provider with more than 1 million customers at the time, copped to hijacking user-search queries made using the Google toolbar within Firefox. Users who believed they had set the browser to the search engine of their choice were redirected to Windstream’s own search portal and results.

MetroPCS: In 2011, MetroPCS, at the time one of the top-five U.S. wireless carriers, announced plans to block streaming video over its 4G network from all sources except YouTube. MetroPCS then threw its weight behind Verizon’s court challenge against the FCC’s 2010 open internet ruling, hoping that rejection of the agency’s authority would allow the company to continue its anti-consumer practices.

PAXFIRE: In 2011, the Electronic Frontier Foundation found that several small ISPs were redirecting search queries via the vendor Paxfire. The ISPs identified in the initial Electronic Frontier Foundation report included Cavalier, Cogent, Frontier, Fuse, DirecPC, RCN and Wide Open West. Paxfire would intercept a person’s search request at Bing and Yahoo and redirect it to another page. By skipping over the search service’s results, the participating ISPs would collect referral fees for delivering users to select websites.

AT&T, SPRINT and VERIZON: From 2011–2013, AT&T, Sprint and Verizon blocked Google Wallet, a mobile-payment system that competed with a similar service called Isis, which all three companies had a stake in developing.

EUROPE: A 2012 report from the Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications found that violations of Net Neutrality affected at least one in five users in Europe. The report found that blocked or slowed connections to services like VOIP, peer-to-peer technologies, gaming applications and email were commonplace.

VERIZON: In 2012, the FCC caught Verizon Wireless blocking people from using tethering applications on their phones. Verizon had asked Google to remove 11 free tethering applications from the Android marketplace. These applications allowed users to circumvent Verizon’s $20 tethering fee and turn their smartphones into Wi-Fi hot spots. By blocking those applications, Verizon violated a Net Neutrality pledge it made to the FCC as a condition of the 2008 airwaves auction.

AT&T: In 2012, AT&T announced that it would disable the FaceTime video-calling app on its customers’ iPhones unless they subscribed to a more expensive text-and-voice plan. AT&T had one goal in mind: separating customers from more of their money by blocking alternatives to AT&T’s own products.

NETWORK-WIDE: Throughout 2013 and early 2014, people across the country experienced slower speeds when trying to connect to certain kinds of websites and applications. Many complained about underperforming streaming video from sites like Netflix. Others had trouble connecting to video-conference sites and making voice calls over the internet.

The common denominator for all of these problems, unbeknownst to users at the time, was their ISPs’ failure to provide enough capacity for this traffic to make it on to their networks in the first place. In other words, the problem was not congestion on the broadband lines coming into homes and businesses, but at the “interconnection” point where the traffic users’ request from other parts of the internet first comes into the ISPs’ networks.

An Open Technology Institute investigation that drew on the Measurement Lab’s data analysis found these slowdowns were the result of “intentional policies by some of the nation’s largest communications companies, which led to significant, months-long degradation of a consumer product for millions of people.” Major broadband providers, including AT&T, Time Warner Cable and Verizon, deliberately limited the capacity at these interconnection points, effectively throttling the delivery of content to thousands of U.S. businesses and residential customers across the country.

VERIZON: During oral arguments in Verizon v. FCC in 2013, judges asked whether the phone giant would favor some preferred services, content or sites over others if the court overruled the agency’s existing open internet rules. Verizon counsel Helgi Walker had this to say: “I’m authorized to state from my client today that but for these rules we would be exploring those types of arrangements.” Walker’s admission might have gone unnoticed had she not repeated it on at least five separate occasions during arguments.

The court struck down the FCC’s rules in January 2014 — and in May, FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler opened a public proceeding to consider a new order.

In response millions of people urged the FCC to reclassify broadband providers as common carriers and in February 2015, the agency did just that.

Since Trump appointed him in January 2017, FCC Chairman Ajit Pai sought to dismantle the agency’s landmark Net Neutrality rules. In December, the FCC’s Republican majority destroyed all Net Neutrality protections, ignoring the outcry from millions of people.

In the absence of any rules, violations of the open internet will become more and more common.

Don’t believe me? Let history be the guide.

The principle that protects free speech and innovation online is irrelevant, they claim, as blocking has never, ever happened. And if it did, they add, market forces would compel internet service providers to correct course and reopen their networks.

In reality, many providers both in the United States and abroad have violated the principles of Net Neutrality — and they plan to continue doing so in the future.

Here’s what happens when cable and phone companies are left to their own devices:

MADISON RIVER: In 2005, North Carolina ISP Madison River Communications blocked the voice-over-internet protocol (VOIP) service Vonage. Vonage filed a complaint with the FCC after receiving a slew of customer complaints. The FCC stepped in to sanction Madison River and prevent further blocking, but it lacks the authority to stop this kind of abuse today.

COMCAST: In 2005, the nation’s largest ISP, Comcast, began secretly blocking peer-to-peer technologies that its customers were using over its network. Users of services like BitTorrent and Gnutella were unable to connect to these services. 2007 investigations from the Associated Press, the Electronic Frontier Foundation and others confirmed that Comcast was indeed blocking or slowing file-sharing applications without disclosing this fact to its customers.

TELUS: In 2005, Canada’s second-largest telecommunications company, Telus, began blocking access to a server that hosted a website supporting a labor strike against the company. Researchers at Harvard and the University of Toronto found that this action resulted in Telus blocking an additional 766 unrelated sites.

AT&T: From 2007–2009, AT&T forced Apple to block Skype and other competing VOIP phone services on the iPhone. The wireless provider wanted to prevent iPhone users from using any application that would allow them to make calls on such “over-the-top” voice services. The Google Voice app received similar treatment from carriers like AT&T when it came on the scene in 2009.

WINDSTREAM: In 2010, Windstream Communications, a DSL provider with more than 1 million customers at the time, copped to hijacking user-search queries made using the Google toolbar within Firefox. Users who believed they had set the browser to the search engine of their choice were redirected to Windstream’s own search portal and results.

MetroPCS: In 2011, MetroPCS, at the time one of the top-five U.S. wireless carriers, announced plans to block streaming video over its 4G network from all sources except YouTube. MetroPCS then threw its weight behind Verizon’s court challenge against the FCC’s 2010 open internet ruling, hoping that rejection of the agency’s authority would allow the company to continue its anti-consumer practices.

PAXFIRE: In 2011, the Electronic Frontier Foundation found that several small ISPs were redirecting search queries via the vendor Paxfire. The ISPs identified in the initial Electronic Frontier Foundation report included Cavalier, Cogent, Frontier, Fuse, DirecPC, RCN and Wide Open West. Paxfire would intercept a person’s search request at Bing and Yahoo and redirect it to another page. By skipping over the search service’s results, the participating ISPs would collect referral fees for delivering users to select websites.

AT&T, SPRINT and VERIZON: From 2011–2013, AT&T, Sprint and Verizon blocked Google Wallet, a mobile-payment system that competed with a similar service called Isis, which all three companies had a stake in developing.

EUROPE: A 2012 report from the Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications found that violations of Net Neutrality affected at least one in five users in Europe. The report found that blocked or slowed connections to services like VOIP, peer-to-peer technologies, gaming applications and email were commonplace.

VERIZON: In 2012, the FCC caught Verizon Wireless blocking people from using tethering applications on their phones. Verizon had asked Google to remove 11 free tethering applications from the Android marketplace. These applications allowed users to circumvent Verizon’s $20 tethering fee and turn their smartphones into Wi-Fi hot spots. By blocking those applications, Verizon violated a Net Neutrality pledge it made to the FCC as a condition of the 2008 airwaves auction.

AT&T: In 2012, AT&T announced that it would disable the FaceTime video-calling app on its customers’ iPhones unless they subscribed to a more expensive text-and-voice plan. AT&T had one goal in mind: separating customers from more of their money by blocking alternatives to AT&T’s own products.

NETWORK-WIDE: Throughout 2013 and early 2014, people across the country experienced slower speeds when trying to connect to certain kinds of websites and applications. Many complained about underperforming streaming video from sites like Netflix. Others had trouble connecting to video-conference sites and making voice calls over the internet.

The common denominator for all of these problems, unbeknownst to users at the time, was their ISPs’ failure to provide enough capacity for this traffic to make it on to their networks in the first place. In other words, the problem was not congestion on the broadband lines coming into homes and businesses, but at the “interconnection” point where the traffic users’ request from other parts of the internet first comes into the ISPs’ networks.

An Open Technology Institute investigation that drew on the Measurement Lab’s data analysis found these slowdowns were the result of “intentional policies by some of the nation’s largest communications companies, which led to significant, months-long degradation of a consumer product for millions of people.” Major broadband providers, including AT&T, Time Warner Cable and Verizon, deliberately limited the capacity at these interconnection points, effectively throttling the delivery of content to thousands of U.S. businesses and residential customers across the country.

VERIZON: During oral arguments in Verizon v. FCC in 2013, judges asked whether the phone giant would favor some preferred services, content or sites over others if the court overruled the agency’s existing open internet rules. Verizon counsel Helgi Walker had this to say: “I’m authorized to state from my client today that but for these rules we would be exploring those types of arrangements.” Walker’s admission might have gone unnoticed had she not repeated it on at least five separate occasions during arguments.

The court struck down the FCC’s rules in January 2014 — and in May, FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler opened a public proceeding to consider a new order.

In response millions of people urged the FCC to reclassify broadband providers as common carriers and in February 2015, the agency did just that.

Since Trump appointed him in January 2017, FCC Chairman Ajit Pai sought to dismantle the agency’s landmark Net Neutrality rules. In December, the FCC’s Republican majority destroyed all Net Neutrality protections, ignoring the outcry from millions of people.

In the absence of any rules, violations of the open internet will become more and more common.

Don’t believe me? Let history be the guide.

Tranquility

Well-Known Member

It seems the only difference to us is who gets our money. Nothing is for free.

The pipe people (Phone, cable, wireless) promise to increase bandwidth. The content people promise to...well they promise freedom of access--I guess.

In the time no neutrality, my life has not changed. I still get ads from BBQ makers at work when I dream of a BBQ just before I go to sleep at home. They were always looking, we just didn't pay attention.

The pipe people (Phone, cable, wireless) promise to increase bandwidth. The content people promise to...well they promise freedom of access--I guess.

In the time no neutrality, my life has not changed. I still get ads from BBQ makers at work when I dream of a BBQ just before I go to sleep at home. They were always looking, we just didn't pay attention.

seaofgreens

My Mind Is Free

There is a huge difference.You are asserting that we should desire a tiered internet service, where not only can we not pay for what we want, we just have to accept whatever ISP we prescribe to will not block/slow/censor our shit... Almost nobody wants that aside from those that have been convinced this is all about some free market restriction by the liberals. Nobody is saying everything should be free, just that one party/business should not be favored over another when it comes to access.

Before these restrictions you were almost certainly at one point data throttled or had a search page hijacked to some third party service without you even knowing about it. How would you know if your service was slowed to a specific site? You would have just thought the internet was running slow that day or the site was running slow. It doesn't occur that your ISP might intentionally be trying to re-direct traffic. No ISP will publicly admit to any of that stuff, in fact says they never have done anything like that, and yet we see numerous examples of traffic being shunted or redirected or blocked altogether to favor whatever the ISP wants.

More personalized ads from your data being sold off is of course ethically interesting/debatable, but really doesn't have much to do with net neutrality. Being re-directed to some product when you want to view a google result or view a specific page about some other competing product? Slowing down access to all competing products websites but the one you want sold? That would be in the same ballpark.

Before these restrictions you were almost certainly at one point data throttled or had a search page hijacked to some third party service without you even knowing about it. How would you know if your service was slowed to a specific site? You would have just thought the internet was running slow that day or the site was running slow. It doesn't occur that your ISP might intentionally be trying to re-direct traffic. No ISP will publicly admit to any of that stuff, in fact says they never have done anything like that, and yet we see numerous examples of traffic being shunted or redirected or blocked altogether to favor whatever the ISP wants.

More personalized ads from your data being sold off is of course ethically interesting/debatable, but really doesn't have much to do with net neutrality. Being re-directed to some product when you want to view a google result or view a specific page about some other competing product? Slowing down access to all competing products websites but the one you want sold? That would be in the same ballpark.

Silver420Surfer

Downward spiral

@OldNewbie -IDK, if you responded about getting nothing for free to my comment above it or what.

But I can't see what free has to do with my providing some prior evidence of what companies have tried to do when we had net neutrality in place. This isn't a partisan gripe, or a "watch out, big brother is watching rant. These are good examples of what has already been tried and what we may expect in the future. Nothing as simple as "the difference in who gets our money" at all.

Also, I pay dearly for my measly 100Mb internet connection(gigabit should be standard offer in this day and age), wish it was for free though.

But I can't see what free has to do with my providing some prior evidence of what companies have tried to do when we had net neutrality in place. This isn't a partisan gripe, or a "watch out, big brother is watching rant. These are good examples of what has already been tried and what we may expect in the future. Nothing as simple as "the difference in who gets our money" at all.

Also, I pay dearly for my measly 100Mb internet connection(gigabit should be standard offer in this day and age), wish it was for free though.

Tranquility

Well-Known Member

Some of the "for free" has to do with net neutrality. You are shifting the costs from content providers to the network providers. Content providers get "free" downstream use.@OldNewbie -IDK, if you responded about getting nothing for free to my comment above it or what.

But I can't see what free has to do with my providing some prior evidence of what companies have tried to do when we had net neutrality in place. This isn't a partisan gripe, or a "watch out, big brother is watching rant. These are good examples of what has already been tried and what we may expect in the future. Nothing as simple as "the difference in who gets our money" at all.

Also, I pay dearly for my measly 100Mb internet connection(gigabit should be standard offer in this day and age), wish it was for free though.

I take no real position on which is better but acknowledge Republicans tend towards the network and Democrats tend towards the content. I choose to go to network providers if I have to make a choice because it seems reasonable people pay for what they get. But, if net neutrality comes back, I'm fine with that too. The reason I don't much care is that, contrary to the scare tactics that came out over the fight, I just don't see or anticipate much difference in my access to content. I was told freedom of speech was going to die, freedom of association--dead, free and fair elections now gone, can't start a business, can't choose the products I buy now that net neutrality is gone. It hasn't happened yet. And, I don't predict it will. (At least before other complete controls over us. Like, no currency.)

Yes, things will change. They are going to change no matter what. I've heard the arguments over this for a long time, years perhaps. Neither side has convinced me and both sides can point to bad actors who gain more benefits then fair so I have to fall back on if I want a pipeline to play games with my friends, shouldn't I be able to pay for it rather than wait to see if my neighbor's Netflix slows down the framerate?

As to what you pay for your measly connection, will the connection get better if you pay more to the connectors or to the content providers? We all know U.S. internet infrastructure is insufficient. What is the best way to get investment into improving it?

But, freedom, too.

5:6 pickem.

seaofgreens

My Mind Is Free

Well, it's just like everything else. Best way to improve national infrastructure of any kind is to pool our populations money proportional to the income they receive, and then build said improvement. But instead of that, we would rather shift that responsibility to some corporation, so that they can charge user fees while more than likely tax-dollars are spent in reimbursements or tax ride-offs only available or useful to a conglomerate.

We all already pay monthly on two fronts for infrastructure (wi-fi/ethernet connection and for most, also the wireless 4G connection?) And they can and do charge more or less for your access to what speed is available... so I don't see how that correlates? They still for some reason don't have enough investment to build out into rural areas? I pay $70/month for 10mbps from some rando rural cell tower broadcast... I'd be more than happy to pay that $70 to one of the big companies if they would agree to extend their network my way. Don't see any of them beating down my door. Because there are not many folks where I live, and investing in extending the network to the small population in my area is not worth the investment. Period.

It would take public funding in the interests of providing the whole population the benefit of faster networks to make that happen. Also never going to happen.

So what's going to change when they now have the ability to throttle netflix for me so that my neighbor can play his video game? Not much. Guess I won't be able to watch netflix. But thanks! Freedom and what not. Right?

We all already pay monthly on two fronts for infrastructure (wi-fi/ethernet connection and for most, also the wireless 4G connection?) And they can and do charge more or less for your access to what speed is available... so I don't see how that correlates? They still for some reason don't have enough investment to build out into rural areas? I pay $70/month for 10mbps from some rando rural cell tower broadcast... I'd be more than happy to pay that $70 to one of the big companies if they would agree to extend their network my way. Don't see any of them beating down my door. Because there are not many folks where I live, and investing in extending the network to the small population in my area is not worth the investment. Period.

It would take public funding in the interests of providing the whole population the benefit of faster networks to make that happen. Also never going to happen.

So what's going to change when they now have the ability to throttle netflix for me so that my neighbor can play his video game? Not much. Guess I won't be able to watch netflix. But thanks! Freedom and what not. Right?

Tranquility

Well-Known Member

So, you don't think the person who pays should get the bandwidth?So what's going to change when they now have the ability to throttle netflix for me so that my neighbor can play his video game? Not much. Guess I won't be able to watch netflix. But thanks! Freedom and what not. Right?

Edit:

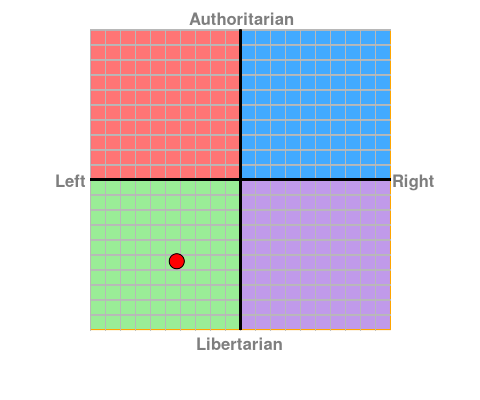

Take the test!

https://www.politicalcompass.org/test

Me?

Last edited:

seaofgreens

My Mind Is Free

That misses the point. I knew I shouldn't have included that last bit as I figured that would be the latching point. (Forget all about the main point, which was that Corporations only fund what makes money, and a nationally upgraded infrastructure is not profitable... so erasing net neutrality does nothing to help expand infrastructure, as is a common argument.)

Lets just say both my neighbor and I use the same service. We both already paid for our bandwidth. In this case lets say we both pay the ISP for up to 10mbps. They all say *up to. No exceptions. But on average, I would assume that I should get about 10mbps service from the infrastructure we both paid into.

This means that now we are moving onto content providers. Lets say I pay Netflix for service, and a neighbor pays for ps4 access. Lets say PS4 then gets a deal to provide their guy with lag free service, and then my *up to goes down accordingly. Neither one of us paid anything different, yet our services changed accordingly. I had no say in the matter, it was all 3rd party actions. Yet things changed for me right?

Is that fair?

I don't know.

Then lets say Netflix gets the same deal. Where does that extra pipe come from? Would my paying netflix even more = better infrastructure to stream their stuff? Who knows? That goes to Netflix. Not the ISP. Will the ISP build better infrastructure? Or just slow down or cut off lets say... Youtube, to get that extra pipe?

It gets tricky, and questions build. The environment gets murky real quick.

So you tell me what's fair, yeah? I never said I have the right answer. Just know a wrong one when I see it.

Here is where I seem to lie along the spectrum:

Lets just say both my neighbor and I use the same service. We both already paid for our bandwidth. In this case lets say we both pay the ISP for up to 10mbps. They all say *up to. No exceptions. But on average, I would assume that I should get about 10mbps service from the infrastructure we both paid into.

This means that now we are moving onto content providers. Lets say I pay Netflix for service, and a neighbor pays for ps4 access. Lets say PS4 then gets a deal to provide their guy with lag free service, and then my *up to goes down accordingly. Neither one of us paid anything different, yet our services changed accordingly. I had no say in the matter, it was all 3rd party actions. Yet things changed for me right?

Is that fair?

I don't know.

Then lets say Netflix gets the same deal. Where does that extra pipe come from? Would my paying netflix even more = better infrastructure to stream their stuff? Who knows? That goes to Netflix. Not the ISP. Will the ISP build better infrastructure? Or just slow down or cut off lets say... Youtube, to get that extra pipe?

It gets tricky, and questions build. The environment gets murky real quick.

So you tell me what's fair, yeah? I never said I have the right answer. Just know a wrong one when I see it.

Here is where I seem to lie along the spectrum:

Last edited:

Tranquility

Well-Known Member

An "upgraded" infrastructure can be profitable. An "expanded" one that promises to have others pay for the pipe that goes to those distant from populations centers, less so.That misses the point. I knew I shouldn't have included that last bit as I figured that would be the latching point. (Forget all about the main point, which was that Corporations only fund what makes money, and a nationally upgraded infrastructure is not profitable... so erasing net neutrality does nothing to help expand infrastructure, as is a common argument.)

The current structure is based on mostly low-use with some high bandwidth people. The low-use currently subsidize the higher usage. Like the gym, pricing is based on average expectations of how many who sign up, because the owner knows many won't go every day all day. T-Mobile is starting to address the difference by giving old guys a discount on phone service. I suspect they know I don't surf on my phone to any extent as compared to those who grew up with a phone.Lets just say both my neighbor and I use the same service. We both already paid for our bandwidth. In this case lets say we both pay the ISP for up to 10mbps. They all say *up to. No exceptions. But on average, I would assume that I should get about 10mbps service from the infrastructure we both paid into.

Let's not go here. There are contractual issues that could be litigated to give the answer. Netflix should not have promised you clean stream if they couldn't make it happen.This means that now we are moving onto content providers. Lets say I pay Netflix for service, and a neighbor pays for ps4 access. Lets say PS4 then gets a deal to provide their guy with lag free service, and then my *up to goes down accordingly. Neither one of us paid anything different, yet our services changed accordingly. I had no say in the matter, it was all 3rd party actions. Yet things changed for me right?

If you could deal with the issue by suing on contract or contacting federal regulators and having them help, which would give the person the fairest result?Is that fair?

I don't know.

This seems the issue. Is bandwidth a zero-sum game? In the short run, essentially, yes. You can't make a bigger pipe in an instant just because demand goes up. Over time, the pipe will adjust to demand. How fast depends on how it is paid for.Then lets say Netflix gets the same deal. Where does that extra pipe come from? Would my paying netflix even more = better infrastructure to stream their stuff? Who knows? That goes to Netflix. Not the ISP. Will the ISP build better infrastructure of just slow down or cut off lets say... Youtube to get that extra pipe?

I think some of the difference gets to your concern over expanding the pipe's reach. Net neutrality is probably better if the goal is to make sure everyone gets the same access no matter where they live. Net neutrality is probably worse if the goal is to make sure those with good access to the pipe get as much bandwidth as they need/want.It gets tricky, and questions build. The environment gets murky real quick.

So you tell me what's fair, yeah? I never said I have the right answer. Just know a wrong one when I see it.

That difference might explain why the general left/right distinction on which path to support.

Tranquility

Well-Known Member

Net neutrality gives corporations complete control over the internet. It means the corporations that control the backbone of the internet may opt to throttle speed for those that can pay more and those that pay less. If you are not a rich person you should be against net neutrality PERIOD. This is all about corporations wanting to extract more money from everyday people in a very unfair way...same as usual.

@OldNewbie you keep comeing up with fun and interesting things, thanks. Here is my grid. Of course it is very close to Gandhi's chart.

I must say that it is what I would have expected. This was a lot of fun.

Gandhi? Do you think you can see your way to stop nuking me?

(By-the-by, @steama you might edit your post. I suspect you mean the opposite to what you wrote.)

Last edited:

Tranquility

Well-Known Member

(Forget all about the main point, which was that Corporations only fund what makes money, and a nationally upgraded infrastructure is not profitable... so erasing net neutrality does nothing to help expand infrastructure, as is a common argument.)

A coincidental reply in the news today:

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/arti...roadband-via-satellite-backed-by-fcc-chairman

Elon Musk’s SpaceX moved closer to another orbital frontier as regulators advanced its application to launch a low-orbit constellation of satellites and join a jostling field of operators trying to cash in on broadband service from space.

Federal Communications Commission Chairman Ajit Pai on Wednesday recommended the agency approve Space Exploration Technologies Corp.’s application to provide broadband services using satellite technologies in the U.S. and on a global basis. The proposal now goes to Pai’s four fellow commissioners for consideration at the agency which earlier approved three international operators for satellite-broadband operations: OneWeb, Space Norway AS and Telesat Canada.

“To bridge America’s digital divide, we’ll have to use innovative technologies,” Pai said in an emailed statement. “Satellite technology can help reach Americans who live in rural or hard-to-serve places where fiber optic cables and cell towers do not reach.”

The FCC’s move comes as U.S. politicians call for improved internet service in rural areas. President Donald Trump’s infrastructure proposal lists broadband, or high-speed internet service, as eligible for funding alongside traditional projects such as roads and bridges. Some Democratic lawmakers have criticized the lack of dedicated broadband funding.

Federal Communications Commission Chairman Ajit Pai on Wednesday recommended the agency approve Space Exploration Technologies Corp.’s application to provide broadband services using satellite technologies in the U.S. and on a global basis. The proposal now goes to Pai’s four fellow commissioners for consideration at the agency which earlier approved three international operators for satellite-broadband operations: OneWeb, Space Norway AS and Telesat Canada.

“To bridge America’s digital divide, we’ll have to use innovative technologies,” Pai said in an emailed statement. “Satellite technology can help reach Americans who live in rural or hard-to-serve places where fiber optic cables and cell towers do not reach.”

The FCC’s move comes as U.S. politicians call for improved internet service in rural areas. President Donald Trump’s infrastructure proposal lists broadband, or high-speed internet service, as eligible for funding alongside traditional projects such as roads and bridges. Some Democratic lawmakers have criticized the lack of dedicated broadband funding.

Silver420Surfer

Downward spiral

Unfortunately many of those in charge of these decisions still think like 7-10Mb connection speeds are "adequate".

Hopefully the gov't doesn't fuck it up like they did with the Verizon FiOs debacle.

Decades Of Failed Promises From Verizon: It Promises Fiber To Get Tax Breaks... Then Never Delivers

from the this-again? dept

I witnessed this 1st hand in Florida while working in the telecommunications industry. We watched Verizon cherry pick the rich neighborhoods and leave the poorer ones for dead. Look at FiOs coverage map in the US to see this yourself. They rolled out tons of migrant workers in the neighborhoods dispatched to mark out where lines would go, junction boxes, etc., and then....never...came back to run the fiber. So they underpaid a bunch of Mexican, 1099 workers, stole our tax monies and disappeared into the sunset with the "profits" all the while declaring they brought broadband to the masses(as long as you lived on the right side of the tracks).

Rather than Expanding Broadband, the FCC Wants to Count Cell Service as Internet

Fudging the numbers doesn’t help anybody.

"For many Americans without access to high-speed INTERNET, their options for getting online are pretty limited: go to the library, go to McDonald's, or eat up their data limit on their cell phone.

Now, in a move that would seriously oversell the number of Americans who have real access to high-speed internet, the Federal Communications Commission is considering including that last option—using your phone's data plan to access the internet—in its definition of "broadband access." In other words, if this change is made, using your phone would be considered just as good as having high-speed fiber to your door.

If this definition were changed, it would be a serious blow to the estimated 19 million Americans who still lack access to high-speed internet. It would effectively reduce the number of those Americans who are considered "unserved," covering up the problem and reducing the incentive for internet service providers to try to reach them."

Hopefully the gov't doesn't fuck it up like they did with the Verizon FiOs debacle.

Decades Of Failed Promises From Verizon: It Promises Fiber To Get Tax Breaks... Then Never Delivers

from the this-again? dept

I witnessed this 1st hand in Florida while working in the telecommunications industry. We watched Verizon cherry pick the rich neighborhoods and leave the poorer ones for dead. Look at FiOs coverage map in the US to see this yourself. They rolled out tons of migrant workers in the neighborhoods dispatched to mark out where lines would go, junction boxes, etc., and then....never...came back to run the fiber. So they underpaid a bunch of Mexican, 1099 workers, stole our tax monies and disappeared into the sunset with the "profits" all the while declaring they brought broadband to the masses(as long as you lived on the right side of the tracks).

Rather than Expanding Broadband, the FCC Wants to Count Cell Service as Internet

Fudging the numbers doesn’t help anybody.

"For many Americans without access to high-speed INTERNET, their options for getting online are pretty limited: go to the library, go to McDonald's, or eat up their data limit on their cell phone.

Now, in a move that would seriously oversell the number of Americans who have real access to high-speed internet, the Federal Communications Commission is considering including that last option—using your phone's data plan to access the internet—in its definition of "broadband access." In other words, if this change is made, using your phone would be considered just as good as having high-speed fiber to your door.

If this definition were changed, it would be a serious blow to the estimated 19 million Americans who still lack access to high-speed internet. It would effectively reduce the number of those Americans who are considered "unserved," covering up the problem and reducing the incentive for internet service providers to try to reach them."