-

SCAM WARNING! See how this scam works in Classifieds.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The 2016 Presidential Candidates Thread

- Thread starter CarolKing

- Start date

His_Highness

In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king

Well.....it's been a sad day here at the Highness household....

Yesterday Bernie 'officially suspended' his run and received some concessions from Hillary, including a large chunk of speech time at the convention (10 to 13 hours depending on the news article you read). I've wanted Bernie to stay in the race and leverage the political capital he has amassed and he has done just that. Way to go Bernie!

Not wanting to appear a sore loser and to show my appreciation and support for Bernie's path (If it was good enough for Bernie, it's good enough for me)........I have 'officially suspended' my household campaigning for Bernie and have congratulated my wife on her nominee's win.

Unity, solidarity and

I call this taking the high road (pun intended).

Yesterday Bernie 'officially suspended' his run and received some concessions from Hillary, including a large chunk of speech time at the convention (10 to 13 hours depending on the news article you read). I've wanted Bernie to stay in the race and leverage the political capital he has amassed and he has done just that. Way to go Bernie!

Not wanting to appear a sore loser and to show my appreciation and support for Bernie's path (If it was good enough for Bernie, it's good enough for me)........I have 'officially suspended' my household campaigning for Bernie and have congratulated my wife on her nominee's win.

Unity, solidarity and

I call this taking the high road (pun intended).

gangababa

Well-Known Member

The Presidential race ought not be a popularity contest; we are voting for a future not a person.

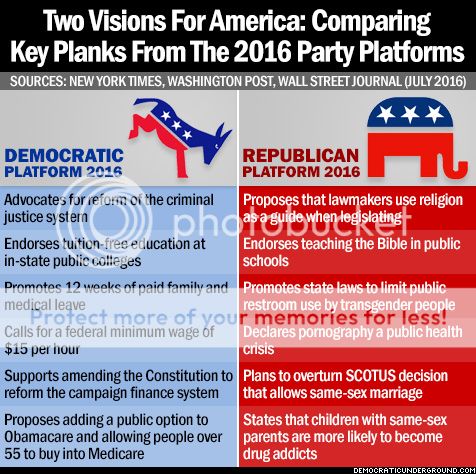

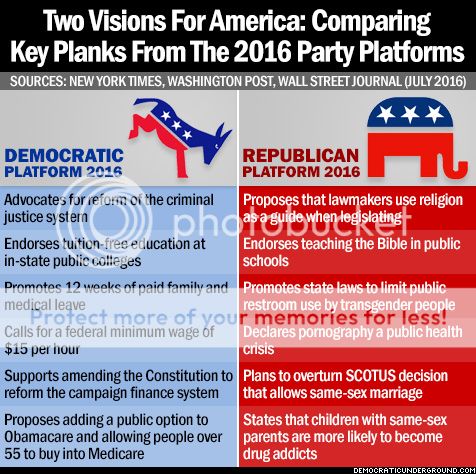

The future proposed by the Republican party and that offered by the Democratic party do differ.

For those who want a country of walls and laws restricting the rights of others, vote Republican.

If you want a world of inclusion and acceptance of diversity, vote Democratic.

Party platforms are not simply fluff; they show the hearts and minds of the people of the parties.

While party platforms don't easily become the template for change, believe the parties when they describe their vision of America and who is a 'real' American.

BTW, the first two Republican ideas in the chart above, are both anti-constitutional.

The future proposed by the Republican party and that offered by the Democratic party do differ.

For those who want a country of walls and laws restricting the rights of others, vote Republican.

If you want a world of inclusion and acceptance of diversity, vote Democratic.

Party platforms are not simply fluff; they show the hearts and minds of the people of the parties.

While party platforms don't easily become the template for change, believe the parties when they describe their vision of America and who is a 'real' American.

BTW, the first two Republican ideas in the chart above, are both anti-constitutional.

neverforget711

Well-Known Member

I'm thinking more like Wrestlemania. Trumpsters know how to throw chairs.Yeah, add Bobby Knight in there. What a hodgepodge of characters with Trump as their leader. DC Comics should pick 'em up immediately. Would even make for a good RPG, eh?

CarolKing

Singer of songs and a vapor connoisseur

Newt and Chris Christie are salivating over the chances of becoming VP for Trump. Mike Pence is the third choice. The Republican Governor of Indiana, he's acting a little more dignified. Of course I don't like any of them.

Who do you think will be Trump's VP? I'm thinking it's going to be Newt. Who will be the lucky couple?

Edit

@His_Highness sometimes it's how we accept defeat that shows character.

Who do you think will be Trump's VP? I'm thinking it's going to be Newt. Who will be the lucky couple?

Edit

@His_Highness sometimes it's how we accept defeat that shows character.

Last edited:

TeeJay1952

Well-Known Member

I saw Barbara Boxer and she said she saw the death of civility occur under Newt's Congress. So Newt because he would be the worst.

cybrguy

Putin is a War Criminal

Newt really was the end of the comity that a well functioning government relies on. We have to get it back, somehow, or we are doomed to have ineffective government indefinitely...

How Newt Gingrich Crippled Congress

No single person bears more responsibility for how much Americans hate Congress than Newt Gingrich. Here’s what he did to it.

By Alex Seitz-Wald

January 30, 2012

How much Americans hate Congress has become cliché. Congress’s approval rating is at an all-time low, and it’s not hard to see why: the institution is broken. Plenty of structural forces have contributed to Congress’s dysfunction: the increasing flow of money in politics, the emergence of the 24/7 cable news cycle, the increasing polarization of the electorate. But perhaps no single person bears as much responsibility as Newt Gingrich.

“I spent 16 years building a majority in the House for the first time since 1954,” Gingrich said during NBC’s Florida GOP debate Monday night, referring to the Republican takeover of the House in 1994. Over those sixteen years of personal and partisan striving, Gingrich invented or perfected many of the things that Americans dislike most about Congress. “I think I am a transformational figure,” Gingrich said before the 1994 election. “I am trying to effect a change so large that the people who would be hurt by the change, the liberal Democratic machine” will fight it, Gingrich explained.

There is no greater pathology in today’s Congress than obstructionism, from Speaker John Boehner’s (R-OH) refusal to raise the debt ceiling in July to Majority Leader Eric Cantor (R-VA) taking disaster relief funds for Hurricane Irene hostage. Both parties have long used Congress’s procedural rules to promote legislation they favor, but Gingrich created something new. “There is the assumption—pioneered by Newt Gingrich himself, as early as the 1970s—that the minority wins when Congress accomplishes less,” Representative Steny Hoyer (D-MD), the number-two Democrat in the House, explained in a 2009 speech at the Center for American Progress Action Fund. “Gingrich’s proposition, and maybe accurately, was that as long as…our party cooperate with Democrats and get 20 or 30 percent of what we want and they get to say they solved the problem and had a bipartisan bill, there’s no incentive for the American people to change leadership,” Hoyer told the Washington Post after the speech. “To some degree, he was proven right in 1994.”

In many ways, the obstructionist minority that Hoyer faced two years ago was following a playbook written by Gingrich over a decade earlier. Gingrich, in fact, took the debt ceiling hostage fifteen years before Boehner did, demanding huge, partisan cuts. In that case, the GOP backed down after President Clinton vetoed their spending bills and Moody’s warned of a credit downgrade. When Boehner refused to raise the debt ceiling, the threat of default lowered the US’s credit rating and was resolved by an complicated process involving a “supercommittee” and a two-step raising of the debt limit over a year. And it was Gingrich who, in one of his first acts as Speaker, patented the practice of refusing to approve disaster relief funds if they weren’t offset with spending cuts. Gingrich even held out after the Oklahoma City bombing later that year, prompting the Philadelphia Daily News to write, “Even Newt Gingrich must lose a little sleep at the idea of making political hay out of the mini-civil war that struck Oklahoma City.”

Of course, Gingrich’s greatest act of obstructionist brinkmanship was the 1995 and 1996 government shutdowns. Thanks to his refusal to concede on spending on social services, the government closed for five days in 1995, longer than the previous eight government shutdowns, and for a whopping twenty-one days a year later—the longest shutdown in history. Thanks to Gingrich’s obstinacy, health and welfare services for veterans were curtailed, Social Security checks were delayed, tens of thousands of visa applications went unprocessed and “numerous sectors of the economy” we negatively impacted, according to the Congressional Research Service.

Then there’s perhaps the most universally reviled practice of Congress: earmarking. Spending on earmarks doubled during Gingrich’s reign as Speaker, rising from $7.8 billion in 1994 to $14.5 billion in 1997. “Speaker Gingrich set in motion the largest explosion of earmarks in the history of Congress,” said Tom Schatz of the conservative group Citizens Against Government Waste. The pork binge was part of a Machiavellian plot to use taxpayer dollars to help Republicans get reelected, as Gingrich himself laid out in a 1996 policy memo titled, “Proposed Principles for Analyzing Each Appropriations Bill.” The memo instructed the chairmen of House Appropriation subcommittees to ask themselves if there are “any Republican members” who “need a specific district item in the bill.” This apparently included Gingrich himself, as Cobb County, Georgia, which the Speaker represented, received more federal dollars per resident than any other suburban county in the country in 1995, except for Arlington, Virginia, home of the Pentagon and other federal agencies, and Brevard County, Florida, home to Cape Canaveral and the Kennedy Space Center.

This partisan earmarking has led Representative Jeff Flake (R-AZ), a longtime anti-earmark crusader who has endorsed Mitt Romney, to dub Gingrich “the father of contemporary earmarking. ” Senator John McCain (R-AZ) went even further on a Romney campaign conference call Wednesday, saying that Gingrich’s plan to “distribute these earmarks led directly to the Abramoff scandal, Congressman Bob Ney going to jail and the corruption that I saw with my own eyes.”

Next

How Newt Gingrich Crippled Congress

No single person bears more responsibility for how much Americans hate Congress than Newt Gingrich. Here’s what he did to it.

By Alex Seitz-Wald

January 30, 2012

How much Americans hate Congress has become cliché. Congress’s approval rating is at an all-time low, and it’s not hard to see why: the institution is broken. Plenty of structural forces have contributed to Congress’s dysfunction: the increasing flow of money in politics, the emergence of the 24/7 cable news cycle, the increasing polarization of the electorate. But perhaps no single person bears as much responsibility as Newt Gingrich.

“I spent 16 years building a majority in the House for the first time since 1954,” Gingrich said during NBC’s Florida GOP debate Monday night, referring to the Republican takeover of the House in 1994. Over those sixteen years of personal and partisan striving, Gingrich invented or perfected many of the things that Americans dislike most about Congress. “I think I am a transformational figure,” Gingrich said before the 1994 election. “I am trying to effect a change so large that the people who would be hurt by the change, the liberal Democratic machine” will fight it, Gingrich explained.

There is no greater pathology in today’s Congress than obstructionism, from Speaker John Boehner’s (R-OH) refusal to raise the debt ceiling in July to Majority Leader Eric Cantor (R-VA) taking disaster relief funds for Hurricane Irene hostage. Both parties have long used Congress’s procedural rules to promote legislation they favor, but Gingrich created something new. “There is the assumption—pioneered by Newt Gingrich himself, as early as the 1970s—that the minority wins when Congress accomplishes less,” Representative Steny Hoyer (D-MD), the number-two Democrat in the House, explained in a 2009 speech at the Center for American Progress Action Fund. “Gingrich’s proposition, and maybe accurately, was that as long as…our party cooperate with Democrats and get 20 or 30 percent of what we want and they get to say they solved the problem and had a bipartisan bill, there’s no incentive for the American people to change leadership,” Hoyer told the Washington Post after the speech. “To some degree, he was proven right in 1994.”

In many ways, the obstructionist minority that Hoyer faced two years ago was following a playbook written by Gingrich over a decade earlier. Gingrich, in fact, took the debt ceiling hostage fifteen years before Boehner did, demanding huge, partisan cuts. In that case, the GOP backed down after President Clinton vetoed their spending bills and Moody’s warned of a credit downgrade. When Boehner refused to raise the debt ceiling, the threat of default lowered the US’s credit rating and was resolved by an complicated process involving a “supercommittee” and a two-step raising of the debt limit over a year. And it was Gingrich who, in one of his first acts as Speaker, patented the practice of refusing to approve disaster relief funds if they weren’t offset with spending cuts. Gingrich even held out after the Oklahoma City bombing later that year, prompting the Philadelphia Daily News to write, “Even Newt Gingrich must lose a little sleep at the idea of making political hay out of the mini-civil war that struck Oklahoma City.”

Of course, Gingrich’s greatest act of obstructionist brinkmanship was the 1995 and 1996 government shutdowns. Thanks to his refusal to concede on spending on social services, the government closed for five days in 1995, longer than the previous eight government shutdowns, and for a whopping twenty-one days a year later—the longest shutdown in history. Thanks to Gingrich’s obstinacy, health and welfare services for veterans were curtailed, Social Security checks were delayed, tens of thousands of visa applications went unprocessed and “numerous sectors of the economy” we negatively impacted, according to the Congressional Research Service.

Then there’s perhaps the most universally reviled practice of Congress: earmarking. Spending on earmarks doubled during Gingrich’s reign as Speaker, rising from $7.8 billion in 1994 to $14.5 billion in 1997. “Speaker Gingrich set in motion the largest explosion of earmarks in the history of Congress,” said Tom Schatz of the conservative group Citizens Against Government Waste. The pork binge was part of a Machiavellian plot to use taxpayer dollars to help Republicans get reelected, as Gingrich himself laid out in a 1996 policy memo titled, “Proposed Principles for Analyzing Each Appropriations Bill.” The memo instructed the chairmen of House Appropriation subcommittees to ask themselves if there are “any Republican members” who “need a specific district item in the bill.” This apparently included Gingrich himself, as Cobb County, Georgia, which the Speaker represented, received more federal dollars per resident than any other suburban county in the country in 1995, except for Arlington, Virginia, home of the Pentagon and other federal agencies, and Brevard County, Florida, home to Cape Canaveral and the Kennedy Space Center.

This partisan earmarking has led Representative Jeff Flake (R-AZ), a longtime anti-earmark crusader who has endorsed Mitt Romney, to dub Gingrich “the father of contemporary earmarking. ” Senator John McCain (R-AZ) went even further on a Romney campaign conference call Wednesday, saying that Gingrich’s plan to “distribute these earmarks led directly to the Abramoff scandal, Congressman Bob Ney going to jail and the corruption that I saw with my own eyes.”

Next

cybrguy

Putin is a War Criminal

More...

Meanwhile, Gingrich was busy creating the climate of nearly nihilistic partisanship that reigns today. In May of 1988, against the wishes of the more moderate GOP leadership, Gingrich brought ethics charges against then-Democratic Speaker Jim Wright relating to a book deal. “This was very much Newt’s initiative,” John Pitney, a professor at Claremont McKenna College who has studied Gingrich for years, told The Nation. Gingrich successfully forced Wright to resign “and that really, for the first time, kind of politicized the entire ethics process,” Larry Evans, a government professor at the College of William and Mary in Virginia, told NPR in December. Ten years later, Gingrich was brought down by a similarly politically charged ethics process, when he was fined $300,000 for flouting tax laws with a tax-exempt college class that Democrats charged was actually political propaganda.

Before Wright, Gingrich tussled with another Democratic speaker and made a name for himself by exploiting the media and the new medium of C-SPAN. Gingrich was sworn in to his first term just a few months before C-SPAN went on the air in 1979, and as an ambitious freshman, he quickly realized the network’s potential. He and a small cadre of young Republicans he led pilloried then-Democratic Speaker Tip O’Neill and other Democratic lawmakers nightly with personal attacks, no matter how unfair, like when he accused the Speaker of putting “communist propaganda” in the Speaker’s lobby.

O’Neill was so irritated by Gingrich’s speeches that he once ordered the House cameras to pan across the empty House chamber to expose that Gingrich was speaking to no one but the cameras, and called Gingrich’s exploits “the lowest thing that I’ve ever seen in my 32 years in Congress. Gingrich fired back that O’Neil was coming “all too close to resembling a McCarthyism of the Left.” The resulting the two-hour exchange, which was covered on every broadcast news outlet that night, made Gingrich into a national hero for conservatives and a villain to liberals.

It was the “moment that made Gingrich,” as Pitney wrote on his blog, and set the mold of punching up in the media that ambitious upstart firebrands like Representative Michele Bachmann (R-MN) would follow for years to come.”If you’re not in the Washington Post every day, you might as well not exist,” Gingrich told Newsweek in the late 80s.

With his newfound fame and a small army of fiery conservative lawmakers behind him—the so-called Conservative Opportunity Society Gingrich created formed in 1983—Gingrich set out to remake the GOP. He narrowly won an election to be House minority whip in 1989 over a more moderate Republican from Illinois and with this official position, he ventured to “build a much more aggressive, activist party,” as he put it. He beefed up the party’s fundraising and recruiting operations to get more Republicans elected and hired pollster Frank Luntz to manage the party’s messaging. Five years later, Gingrich led a wave of fifty-four new Republicans into the House and was elected Speaker.

Of course, Gingrich’s greatest act of punching up would have to wait until he was Speaker, when he exploited Congressional power to impeach President Clinton for having an affair while he himself was having an affair with his current wife Callista. When Univision correspondent Jorge Ramos asked Gingrich about this hypocrisy Wednesday, Gingrich replied, “No, I criticized President Clinton for lying under oath in front of a federal judge, committing perjury—which is a felony for which normal people go to jail.” But as Clinton’s overwhelming popularity today attests, Gingrich’s crusade lacked merit and was plainly political. “Their efforts have succeeded only in turning a serious constitutional process into a partisan process that demeaned both the House and the Senate and became a painful ordeal for the entire country,” Senator Ted Kennedy (D-MA) said at the time.

Just as important, but often overlooked today, is the way in which Gingrich centralized power in party leadership. Progressive Democrats, frustrated with Southern conservative Democrats’ controlling committee chairmanships, started this trend in 1970s, Pitney said, but Gingrich consolidated power in himself to an unprecedented degree by making it so the Speaker could appoint key committee chairmanships. This allowed him to tightly control the agenda and sideline dissident factions in his party in a way that every Speaker since has exploited. “There was a lot of heightened partisanship on both sides, but Gingrich was very vivid, was very much a part of this process” of polarization, Pitney told The Nation.

In another structural change that persists to this day, Gingrich shortened the Congressional workweek to three days in order to maximize fundraising opportunities and provide more contact with constituents. But this also cut down on the amount of time lawmakers spent together in Washington where they could make personal connections across the aisle.

All together, Gingrich’s emphasis on partisan warfare über alles sped the demise of the comity that is essential to the functioning of Congress. If the parties refuse to work together, little can be achieved without super-majorities. It was Gingrich who made winning, rather than good governance, the chief currency of success. Earlier this month, James Lardner laid out in this magazine a proposal to roll back much of Gingrich’s work and fix Congress—but now Gingrich is campaigning to takeover another branch of government. One can only imagine the damage he might inflict there.

Meanwhile, Gingrich was busy creating the climate of nearly nihilistic partisanship that reigns today. In May of 1988, against the wishes of the more moderate GOP leadership, Gingrich brought ethics charges against then-Democratic Speaker Jim Wright relating to a book deal. “This was very much Newt’s initiative,” John Pitney, a professor at Claremont McKenna College who has studied Gingrich for years, told The Nation. Gingrich successfully forced Wright to resign “and that really, for the first time, kind of politicized the entire ethics process,” Larry Evans, a government professor at the College of William and Mary in Virginia, told NPR in December. Ten years later, Gingrich was brought down by a similarly politically charged ethics process, when he was fined $300,000 for flouting tax laws with a tax-exempt college class that Democrats charged was actually political propaganda.

Before Wright, Gingrich tussled with another Democratic speaker and made a name for himself by exploiting the media and the new medium of C-SPAN. Gingrich was sworn in to his first term just a few months before C-SPAN went on the air in 1979, and as an ambitious freshman, he quickly realized the network’s potential. He and a small cadre of young Republicans he led pilloried then-Democratic Speaker Tip O’Neill and other Democratic lawmakers nightly with personal attacks, no matter how unfair, like when he accused the Speaker of putting “communist propaganda” in the Speaker’s lobby.

O’Neill was so irritated by Gingrich’s speeches that he once ordered the House cameras to pan across the empty House chamber to expose that Gingrich was speaking to no one but the cameras, and called Gingrich’s exploits “the lowest thing that I’ve ever seen in my 32 years in Congress. Gingrich fired back that O’Neil was coming “all too close to resembling a McCarthyism of the Left.” The resulting the two-hour exchange, which was covered on every broadcast news outlet that night, made Gingrich into a national hero for conservatives and a villain to liberals.

It was the “moment that made Gingrich,” as Pitney wrote on his blog, and set the mold of punching up in the media that ambitious upstart firebrands like Representative Michele Bachmann (R-MN) would follow for years to come.”If you’re not in the Washington Post every day, you might as well not exist,” Gingrich told Newsweek in the late 80s.

With his newfound fame and a small army of fiery conservative lawmakers behind him—the so-called Conservative Opportunity Society Gingrich created formed in 1983—Gingrich set out to remake the GOP. He narrowly won an election to be House minority whip in 1989 over a more moderate Republican from Illinois and with this official position, he ventured to “build a much more aggressive, activist party,” as he put it. He beefed up the party’s fundraising and recruiting operations to get more Republicans elected and hired pollster Frank Luntz to manage the party’s messaging. Five years later, Gingrich led a wave of fifty-four new Republicans into the House and was elected Speaker.

Of course, Gingrich’s greatest act of punching up would have to wait until he was Speaker, when he exploited Congressional power to impeach President Clinton for having an affair while he himself was having an affair with his current wife Callista. When Univision correspondent Jorge Ramos asked Gingrich about this hypocrisy Wednesday, Gingrich replied, “No, I criticized President Clinton for lying under oath in front of a federal judge, committing perjury—which is a felony for which normal people go to jail.” But as Clinton’s overwhelming popularity today attests, Gingrich’s crusade lacked merit and was plainly political. “Their efforts have succeeded only in turning a serious constitutional process into a partisan process that demeaned both the House and the Senate and became a painful ordeal for the entire country,” Senator Ted Kennedy (D-MA) said at the time.

Just as important, but often overlooked today, is the way in which Gingrich centralized power in party leadership. Progressive Democrats, frustrated with Southern conservative Democrats’ controlling committee chairmanships, started this trend in 1970s, Pitney said, but Gingrich consolidated power in himself to an unprecedented degree by making it so the Speaker could appoint key committee chairmanships. This allowed him to tightly control the agenda and sideline dissident factions in his party in a way that every Speaker since has exploited. “There was a lot of heightened partisanship on both sides, but Gingrich was very vivid, was very much a part of this process” of polarization, Pitney told The Nation.

In another structural change that persists to this day, Gingrich shortened the Congressional workweek to three days in order to maximize fundraising opportunities and provide more contact with constituents. But this also cut down on the amount of time lawmakers spent together in Washington where they could make personal connections across the aisle.

All together, Gingrich’s emphasis on partisan warfare über alles sped the demise of the comity that is essential to the functioning of Congress. If the parties refuse to work together, little can be achieved without super-majorities. It was Gingrich who made winning, rather than good governance, the chief currency of success. Earlier this month, James Lardner laid out in this magazine a proposal to roll back much of Gingrich’s work and fix Congress—but now Gingrich is campaigning to takeover another branch of government. One can only imagine the damage he might inflict there.

grokit

well-worn member

So... it didn't take long for notorious rbg to get under drumpf's skin:

So... it didn't take long for notorious rbg to get under drumpf's skin:Thin-Skinned GOP Crybaby Goes Nuclear, Trump Wants Ginsberg To Resign

Donald Trump flips out over recent criticism from Supreme Court Justice Ginsberg.

Donald Trump is super mad. He is so mad that he is claiming that Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg is not allowed to have personal opinions about candidates. Especially when that personal opinion is solidly anti-Trump–even though that opinion is held by about 60 percent of the nation. The man who would be the tantrum-thrower-in-chief is crying to anyone who will listen because she dared criticize him.

His response to her criticism?

I think it’s highly inappropriate that a United States Supreme Court judge gets involved in a political campaign, frankly. I think it’s a disgrace to the court and I think she should apologize to the court. I couldn’t believe it when I saw it. And I would hope that she would get off the court as soon as possible.

Trump hits back at Ruth Bader Ginsburg, says her comments are a "disgrace," should apologize https://t.co/GqM5JpFiEa pic.twitter.com/62cWz9uNOZ

— Bradd Jaffy (@BraddJaffy) July 12, 2016

Never mind that she didn’t “become involved” in anyone’s campaign, is allowed personal opinions, and (like every American citizen) is within her rights to back a candidate. None of that helps him hurt her for being a big meany head, so it seems he has ignored it. These comments were made, not in her official capacity, and not from the bench, but during two interviews covering her personal opinions.

Oh, and by the way, the late Antonin Scalia was pretty famous for sharing just such opinions.

Donald Trump is often flabbergasted, then unhinged and explosive when facing criticism; losing his cool is pretty much par for the course. Name-calling, hateful lies, and caustic rhetoric often follow anything that Trump feels is unfair. His current tantrum brings to mind a querulous Queen of Hearts losing her temper and screaming for heads, because someone had the gall not to curtsy quite right.

Ginsberg’s comments in two different interviews left no doubt that she doesn’t want to think about, and just plain can’t imagine, a Trump presidency. She made it clear that while for the country it would be only 4 years, his time would reverberate in the Supreme Court for a very, very long time.

She told the NYT:

“I can’t imagine what this place would be — I can’t imagine what the country would be — with Donald Trump as our president, for the country, it could be four years. For the court, it could be — I don’t even want to contemplate that.”

She then called him a “faker” (which is something that he has bragged about in his books) and managed to mention most of his incredible weaknesses, including that he has seemingly gotten away with not releasing his tax returns. That blatant lack of transparency is something the mainstream media seems to be treating with kid gloves when they need to be pulling out boxing gloves.

She said to CNN:

“He is a faker. He has no consistency about him. He says whatever comes into his head at the moment. He really has an ego. … How has he gotten away with not turning over his tax returns? The press seems to be very gentle with him on that.”

If there is something that is predictable about Trump, it is that he can not handle any form of criticism. He takes every small thing personally and launches scorched-Earth reprisals that are heavy with hyperbole, rhetoric, and out -and-out lies. Conspiracy theories, rumors, and innuendo are tools of his trade; and he uses them without compunction, even as he runs for the presidency.

He uses racism, hatred, and fear like an arsonist uses accelerants–liberally and secretively at once, but always with maximum damage, destruction, and deniability as a goal. Not that he would ever take responsibility for his own actions; not when he has no problem denying what he has said and done on the national stage ON CAMERA. Muslims, Mexicans, women, the disabled, low-income families — all have been victims of Trump’s casual supremacist attitudes.

Ginsberg is right: Trump is a nightmare for America. However, he seems to want to destroy, oust, belittle or threaten anyone that speaks out against him. His tactics are that of a school-yard bully; and if he thinks he will be able to damage Ginsberg’s reputation because he is butt-hurt that she spoke the truth, he has another think coming.

The “Notorious RBG,” has more class in one of her lace collars than he has ever been able to purchase in his skeevy life; and she has earned the respect of the nation. He is an infomercial gone wrong, right up until that unthinkable possibility that he be given the nuclear launch codes and Supreme Court picks — then he is a Oligarchist, and an Authoritarian whose track record for dealing with hurt feelings doesn’t bode well for the continued survival of the planet.

http://samuel-warde.com/2016/07/thin-skinned-gop-crybaby-trump-wants-ginsberg-resign/

Last edited:

grokit

well-worn member

I did a little research, and jesse ventura has NOT endorsed mr. drumpf.

He was undecided between drumpf and sanders quite a few months ago, but since he doesn't like nazis and he isn't being considered for vp by either candidate, he came to his senses and went libertarian.

If anyone remembers, ventura was a member of perot's reform party when he was governor of minnesota.

"I like everything Gary Johnson has said so far. He's fiscally conservative and socially liberal – something neither Democrats nor Republicans can offer. He also has a solid plan for bringing our troops home and restoring our economy. And, like me, he's a firm believer that marijuana should be legal.

"I know Gary Johnson personally — we were governors at the same time. He was always an honest, straightforward kind of guy who put the needs of the people first. That's the kind of person I want for our next president."

He was undecided between drumpf and sanders quite a few months ago, but since he doesn't like nazis and he isn't being considered for vp by either candidate, he came to his senses and went libertarian.

If anyone remembers, ventura was a member of perot's reform party when he was governor of minnesota.

"I like everything Gary Johnson has said so far. He's fiscally conservative and socially liberal – something neither Democrats nor Republicans can offer. He also has a solid plan for bringing our troops home and restoring our economy. And, like me, he's a firm believer that marijuana should be legal.

"I know Gary Johnson personally — we were governors at the same time. He was always an honest, straightforward kind of guy who put the needs of the people first. That's the kind of person I want for our next president."

Last edited:

CarolKing

Singer of songs and a vapor connoisseur

Bill Maher alert. Off topic - but Bill will be on Hardball today. 4:00 Pacific Time. I'm sure it will be interesting.

I think Ruth Bader Ginsberg knows exactly what she's doing. Trump is so typical. I think he's

Edit

It looks like Trump's children will have a say in his choices. Probably because they are smarter and better mannered then he is. It's like Trump and his family have taken over the Republican Party. Normally the party makes a lot of the decisions about the convention and the VP. It's so odd. It's like the rest of the Rep party has backed away.

Edit again

I fixed the time for Hardball up above

I think Ruth Bader Ginsberg knows exactly what she's doing. Trump is so typical. I think he's

Edit

It looks like Trump's children will have a say in his choices. Probably because they are smarter and better mannered then he is. It's like Trump and his family have taken over the Republican Party. Normally the party makes a lot of the decisions about the convention and the VP. It's so odd. It's like the rest of the Rep party has backed away.

Edit again

I fixed the time for Hardball up above

Last edited:

cybrguy

Putin is a War Criminal

I don't know if you have ever experienced what happens when the bonfire/campfire you have made turns out to be a lot hotter than you expect. When that happens, your only choice to keep from getting burned is to move back out of the way until the fire burns down a little.Normally the party makes a lot of the decisions about the convention and the VP. It's so odd. It's like the rest of the Rep party has backed away.

I think that is a reasonable analogy for what is happening in the Republican party. I think the majority in the party are afraid of getting burned, and their only option is to back off and say, "Who me? I didn't do that. Ask Donald..."

t-dub

Vapor Sloth

No I can't. I don't believe I have ever seen a candidate like Trump in my lifetime. He is quite unusual and this may be why he captured my attention for a while. This whole race has turned into a dumpster fire. I hate both sides and the libertarians, although they are gaining ground, are still a long ways away from being viable . . .Can you imagine President Obama saying something like ...she should resign, her mind is gone, etc.?

Go O DUCKS!!!No I can't. I don't believe I have ever seen a candidate like Trump in my lifetime. He is quite unusual and this may be why he captured my attention for a while. This whole race has turned into a dumpster fire. I hate both sides and the libertarians, although they are gaining ground, are still a long ways away from being viable . . .

grokit

well-worn member

My dream ticket would be sanders and venturaI did a little research, and jesse ventura has NOT endorsed mr. drumpf.

He was undecided between drumpf and sanders quite a few months ago, but since he doesn't like nazis and he isn't being considered for vp by either candidate, he came to his senses and went libertarian.

If anyone remembers, ventura was a member of perot's reform party when he was governor of minnesota.

"I like everything Gary Johnson has said so far. He's fiscally conservative and socially liberal – something neither Democrats nor Republicans can offer. He also has a solid plan for bringing our troops home and restoring our economy. And, like me, he's a firm believer that marijuana should be legal.

"I know Gary Johnson personally — we were governors at the same time. He was always an honest, straightforward kind of guy who put the needs of the people first. That's the kind of person I want for our next president."

As the ultimate populist/progressive "tag team" they would fix what ails this country,

or die trying

!

!MinnBobber

Well-Known Member

..................................................My dream ticket would be sanders and ventura

As the ultimate populist/progressive "tag team" they would fix what ails this country,

or die trying!

Be careful what you wish for!! Have you lived under Jesse V as Governor? I have and I voted for him BUT said to myself, if he gets elected he'll either be the best gov ever or the worst. IMO, he became the worst gov ever, unfortunately.

Too many steroids???

When he had a radio show here before becoming gov, he would dish out the criticism of government officials at volume 10X. As Gov, if someone criticized him at volume 1X, he would go F'in ballistic. He could dish it out with the best of them BUT couldn't take 1/10 of what he dished out.

Plus, not happy with him suing Kyle the sniper's wife for the book Kyle wrote, and reference to decking someone (that someone being Jesse). He claimed that singular negative language spoiled his stellar career--- WTF??? He was an over the hill actor, and governor who cashed in on being gov and forrner wrestler ( $!,000,000 ?? to ref a match as gov)?? Wah, wah, wah, you big baby.

He got multi-million award BUT now it's been overturned and new trial is needed.

IMO, he has something in common with MN current Gov Dayton but not PC to say it.....

Silat

When the Facts Change, I Change My Mind.

..................................................

Plus, not happy with him suing Kyle the sniper's wife for the book Kyle wrote, and reference to decking someone (that someone being Jesse). He claimed that singular negative language spoiled his stellar career--- WTF??? He was an over the hill actor, and governor who cashed in on being gov and forrner wrestler ( $!,000,000 ?? to ref a match as gov)?? Wah, wah, wah, you big baby.

He got multi-million award BUT now it's been overturned and new trial is needed.

IMO, he has something in common with MN current Gov Dayton but not PC to say it.....

Kyle did lie and that was the point of the suit.

MinnBobber

Well-Known Member

................................................................Kyle did lie and that was the point of the suit.

Ok then,

Jesse called all media "jackals" so they should file a class action suit, that his demeaning remarks hurt their careers....

Kyle's book names no names and what damage did it cause Jesse? Award him $100 and call it square

My point was Jesse said things 100X worse about many folks and they did not sue him.

CarolKing

Singer of songs and a vapor connoisseur

Back to the election.........

At the urging of a donor, Donald Trump called Condoleezza Rice over the weekend to see if she was interested in being his running mate, sources told CNN.

Dana Bash and Elise Labott report that Rice, secretary of state and national security adviser during the George W. Bush Administration, told him she has absolutely no desire to be vice president. It's not the first time she's declared her disinterest; her chief of staff told Politico the same thing last month. With Rice out, the top three contenders are Indiana Gov. Mike Pence (R), former House Speaker Newt Gingrich, and New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie (R). On Wednesday, Trump and his children Ivanka, Don Jr., and Eric had breakfast with Pence at the governor's mansion, and later in the day, Gingrich flew to Indiana to meet with Trump. Christie did not go to Indiana, but did speak with Trump over the phone, and they discussed the vice presidency, CNN reports.

Trump's top aide, Paul Manafort, said Wednesday that Trump will announce his VP pick on Friday. Catherine Garcia

At the urging of a donor, Donald Trump called Condoleezza Rice over the weekend to see if she was interested in being his running mate, sources told CNN.

Dana Bash and Elise Labott report that Rice, secretary of state and national security adviser during the George W. Bush Administration, told him she has absolutely no desire to be vice president. It's not the first time she's declared her disinterest; her chief of staff told Politico the same thing last month. With Rice out, the top three contenders are Indiana Gov. Mike Pence (R), former House Speaker Newt Gingrich, and New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie (R). On Wednesday, Trump and his children Ivanka, Don Jr., and Eric had breakfast with Pence at the governor's mansion, and later in the day, Gingrich flew to Indiana to meet with Trump. Christie did not go to Indiana, but did speak with Trump over the phone, and they discussed the vice presidency, CNN reports.

Trump's top aide, Paul Manafort, said Wednesday that Trump will announce his VP pick on Friday. Catherine Garcia

lwien

Well-Known Member

Trump's top aide, Paul Manafort, said Wednesday that Trump will announce his VP pick on Friday. Catherine Garcia

I have a funny feeling it's gonna be Christie.

cybrguy

Putin is a War Criminal

He can't choose Christie because the bridge gate trials start in Sept, right at the worst time, and there is no way Christie can get away without at least SOME shit getting on him. After all, he either approved it, or he was hands off enough (right) to not know what his number 2 and 3 were spending much of their time on.

I think it will be Pence.

Dogged by scandal, N.J. hates him - Trump can't be serious about Christie as VP | Moran

Star-Ledger Editorial Board

Follow on Twitter

on July 13, 2016 at 5:12 PM, updated July 13, 2016 at 5:40 PM

We won't try to delve into the mind of Donald Trump as he ponders his choice of vice-president. Who knows what we might find? And what's if it's contagious?

But Gov. Chris Christie is on the short list, so those of us who know him best have a patriotic duty to offer Trump some input.

First: If you want to run as a law-and-order candidate, don't pick the guy whose crew faces a felony corruption trial in September.

Christie isn't charged, at least not yet. But his best defense is that he was a clueless chief executive who didn't notice the felonious conspiracy that was unfolding right under his nose.

It could get much worse. Prosecutors are hiding a list of unindicted co-conspirators, people whom they believe participated in this scheme. There's a good chance those names will be revealed during the trial.

Christie knows exactly why Donald Trump's attack on a Mexican-American judge was so wrong. But he's defending Trump's bigotry anyway, as a career move.

What if the governor is on that list? Remember that the crime in the Bridgegate case is not limited to the lane closures. The cover up is part of the alleged conspiracy.

That means Christie will face questions about those deleted text messages, the dozen he exchanged with a senior aide at the precise moment when the bogus cover story about a "traffic study" was being smashed to pieces in the Legislature. Christie says he can't remember the contents of those texts. Hmmm.

Let's say those deleted texts are gone forever. Imagine Christie trying to criticize Hillary Clinton over her use of a private e-mail server?

Let's assume he survives that, too. It's still not over.

One of the defendants, former deputy chief of staff Bridget Kelly, intends to prove that others in the administration knew about the lane closures, according to her lawyer, Michael Critchley.

He didn't name names, but for that tactic to work at trial, one presumes she would have to point the finger up the chain of command, not down.

And it's not like there are 10 layers between her and the governor. Her boss reported directly to Christie.

Kelly is just one of the wild cards. David Wildstein, Christie's #2 at the Port Authority, has pleaded guilty. That means he's probably going to sing on the witness stand in hopes of avoiding prison. What will he say about his former friend, the governor, whom he now hates?

David Samson presents another threat. He reportedly strong-armed United Airlines into providing a direct flight just for him, to ease his trip to his weekend home in South Carolina. United fired its CEO over the scandal, so prosecutors may be coming at Samson soon. He probably knows a secret or two to deal as well.

The purge at United Airlines signals that an indictment is coming against David Samson, Christie's confidante. This could put a struggling campaign out of its misery.

Maybe Christie will dodge all these bullets. Maybe his clueless defense will stand up, for what that's worth.

But why take that chance?

Yes, we understand the core problem: Most Republicans would rather sit out this storm rather than earn the eternal scorn of so many Muslims, Mexicans, women, and people who believe in things like the rule of law and the importance of facts.

When you look at the list of Republicans who find Trump so repugnant they will not attend the convention, it's stuffed with former presidents and governors, along with a truckload of sitting legislators.

Christie's advantage is that he has no shame. He told us in New Hampshire what he really thinks of Trump, that he's a blowhard who is not remotely qualified to be president. Now he swallows Trump's most vile nonsense like it's candy. It is a pathetic thing to watch, really.

Oh, and this. Christie's made a mess of New Jersey during his six-plus years in office, and almost everyone here hates him by now.

So let's sum up: The governor is one step ahead of scandal. He can claim no great accomplishments. And he's proven that he's willing to say just about anything to advance his blind ambition.

Uh-oh. This could be a perfect match.

I think it will be Pence.

Dogged by scandal, N.J. hates him - Trump can't be serious about Christie as VP | Moran

Star-Ledger Editorial Board

Follow on Twitter

on July 13, 2016 at 5:12 PM, updated July 13, 2016 at 5:40 PM

We won't try to delve into the mind of Donald Trump as he ponders his choice of vice-president. Who knows what we might find? And what's if it's contagious?

But Gov. Chris Christie is on the short list, so those of us who know him best have a patriotic duty to offer Trump some input.

First: If you want to run as a law-and-order candidate, don't pick the guy whose crew faces a felony corruption trial in September.

Christie isn't charged, at least not yet. But his best defense is that he was a clueless chief executive who didn't notice the felonious conspiracy that was unfolding right under his nose.

It could get much worse. Prosecutors are hiding a list of unindicted co-conspirators, people whom they believe participated in this scheme. There's a good chance those names will be revealed during the trial.

Christie knows exactly why Donald Trump's attack on a Mexican-American judge was so wrong. But he's defending Trump's bigotry anyway, as a career move.

What if the governor is on that list? Remember that the crime in the Bridgegate case is not limited to the lane closures. The cover up is part of the alleged conspiracy.

That means Christie will face questions about those deleted text messages, the dozen he exchanged with a senior aide at the precise moment when the bogus cover story about a "traffic study" was being smashed to pieces in the Legislature. Christie says he can't remember the contents of those texts. Hmmm.

Let's say those deleted texts are gone forever. Imagine Christie trying to criticize Hillary Clinton over her use of a private e-mail server?

Let's assume he survives that, too. It's still not over.

One of the defendants, former deputy chief of staff Bridget Kelly, intends to prove that others in the administration knew about the lane closures, according to her lawyer, Michael Critchley.

He didn't name names, but for that tactic to work at trial, one presumes she would have to point the finger up the chain of command, not down.

And it's not like there are 10 layers between her and the governor. Her boss reported directly to Christie.

Kelly is just one of the wild cards. David Wildstein, Christie's #2 at the Port Authority, has pleaded guilty. That means he's probably going to sing on the witness stand in hopes of avoiding prison. What will he say about his former friend, the governor, whom he now hates?

David Samson presents another threat. He reportedly strong-armed United Airlines into providing a direct flight just for him, to ease his trip to his weekend home in South Carolina. United fired its CEO over the scandal, so prosecutors may be coming at Samson soon. He probably knows a secret or two to deal as well.

The purge at United Airlines signals that an indictment is coming against David Samson, Christie's confidante. This could put a struggling campaign out of its misery.

Maybe Christie will dodge all these bullets. Maybe his clueless defense will stand up, for what that's worth.

But why take that chance?

Yes, we understand the core problem: Most Republicans would rather sit out this storm rather than earn the eternal scorn of so many Muslims, Mexicans, women, and people who believe in things like the rule of law and the importance of facts.

When you look at the list of Republicans who find Trump so repugnant they will not attend the convention, it's stuffed with former presidents and governors, along with a truckload of sitting legislators.

Christie's advantage is that he has no shame. He told us in New Hampshire what he really thinks of Trump, that he's a blowhard who is not remotely qualified to be president. Now he swallows Trump's most vile nonsense like it's candy. It is a pathetic thing to watch, really.

Oh, and this. Christie's made a mess of New Jersey during his six-plus years in office, and almost everyone here hates him by now.

So let's sum up: The governor is one step ahead of scandal. He can claim no great accomplishments. And he's proven that he's willing to say just about anything to advance his blind ambition.

Uh-oh. This could be a perfect match.

Last edited:

Silat

When the Facts Change, I Change My Mind.

................................................................

Ok then,

Jesse called all media "jackals" so they should file a class action suit, that his demeaning remarks hurt their careers....

Kyle's book names no names and what damage did it cause Jesse? Award him $100 and call it square

My point was Jesse said things 100X worse about many folks and they did not sue him.

Again facts matter. The court found that Kyle lied.

Your comments about him being worse have nothing to do with it.

And Kyle lied about his medal count also.